The Changing Life of Radio Broadcast and David Ayres’ Miracle

I was a little shaken up when I learned that the radio broadcasts of Oakland A’s games would no longer be heard on traditional over-the-air radio in that city.

The fortunes of the A’s would be picked up on a streaming app via the Internet, and for their fans in Sacramento, 90 miles away, but not in the city where the team actually plays their games.

I rapidly thought of what it would have been like if I couldn’t listen to the team I followed for several years, the New York Giants, when they played in the Polo Grounds before their move to San Francisco. Or the other two teams in New York, the Brooklyn Dodgers, and the Yankees.

I’ll bet my love of sports wouldn’t have flourished, and perhaps my career would have gone in a different direction. My life in sports broadcasting has been virtually all about television, but baseball is really about the radio broadcasts. For me, and all those who followed their local teams, both in the major leagues and the minors, the thrill of tuning into a ballgame was a thrill beyond compare.

Radio time

You see, it was all about imagination. The thread of these broadcasts, described by your favorite announcers, set the tone for the game that ensued. In many ways, it is why I appreciate reading books, perhaps more than watching films. When I read, my imagination takes over. That’s what listening to a baseball game on radio is all about. You hear the crowd, you may even hear the vendors in the stands, the public address announcer in the background, and of course the play-by-play man describing the game. Not only the game, but the weather conditions, the threatening sky, with dark clouds hovering out toward left field. The nuances of the ballpark, if your team is playing on the road.

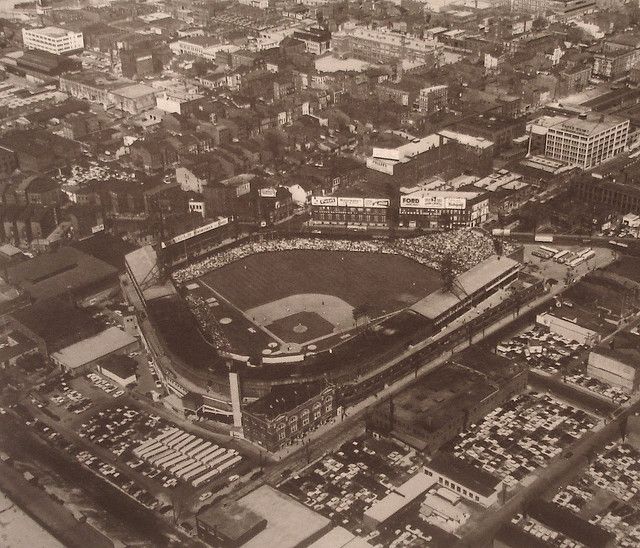

I had a routine when the Giants came on the air. There was a page in the yearbook showing the other National League ballparks in an aerial view. I opened to that page as the broadcast began. If the Giants were playing in Cincinnati, I focused on the photo of Crosley Field. It really didn’t tell me much, other than the shape of the park, but I could put myself right there for the upcoming contest.

Crosley Field

Russ Hodges was the voice of the Giants, and I would live by his every word. He would tell me about the “terrace” in Crosley Field, where the outfield, particularly in left field, would rise up a few feet to the wall. Or the fans sitting in the small bleacher area in right field. If it was a day game, they called it the “sun deck”, at night it was, naturally, the “moon deck”.

Russ Hodges

It was the same for the other ballparks. The “pavillion” in Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis. The high wall in right field that was the trademark in Philadelphia’s Shibe Park. Of course, the ivy covering the outfield wall at Wrigley Field, and the ivy, which also graced a good part of Forbes Field in Pittsburgh.

I could visualize a burly right-handed slugger stepping deep into the batter’s box. Or a diminutive left-handed hitter standing close to the plate, preparing to bunt. It was all there in my mind.

As a youngster under the age of 12, I was puzzled as to why the tarpaulin was covering the field in Chicago, while the sun was blazing outside my house. Or why night games in St.Louis started so late, at 9pm. What did I know about time zones?

So, my life revolved around listening to baseball on the radio. Besides hearing my Giants, I also tuned into Dodger games with Red Barber and a young Vin Scully at the mike, and the American League Yankees, with the great Mel Allen describing what seemed like a victory every day for the pinstripes.

Baseball on radio created an impression that extended to the broadcasts of other sports.

Marty Glickman was the primary voice of many New York sports, including the football Giants, and all of basketball, especially the Knicks and the college games at Madison Square Garden.

What I craved most about those broadcasts was when Glickman described the uniforms teams were wearing. The Giants, in their royal blue home jerseys with silver pants. Or the Boston Celtics, in their home white uniforms with kelly green letters and numerals. I could see it all without pictures.

That’s why the news about the A’s discontinuing local radio broadcasts bothers me.

Somewhere in Oakland, there’s a youngster who won’t be able to experience what I did. Yes, I know, you can see everything on TV, even on your phone.

Let me be clear, I am not living in the past. I think the technology has been sensational. And it’s still getting better. But I wouldn’t give up what baseball on the radio meant for me, for the world.

Shifting gears, it is with great pleasure that I can reveal that Walter Mitty lives. As many of you know, Walter Mitty is a fictional character in James Thurber’s short story, “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty”. Walter Mitty is a mild-mannered man who has a vivid fantasy life. He imagines himself in many exciting life scenarios. He has daydreams that he is a hero in various situations.

Well, we’ve come across a real-life story, not fiction.

In the National Hockey League, there is always an emergency goaltender assigned to every game. Each team has a backup goalie ready to go, in the event of an injury to the starter. But if the starter and the backup both go down, the emergency man, sitting in the stands, is called on to suit up and play. He can play for either team. It all depends on which team needs him.

Last week, the Carolina Hurricanes were hosting the Toronto Maple Leafs. Carolina lost both its goaltenders. Sitting in the stands was 42-year old David Ayres. Ayres was called to get into uniform and tend goal in the second period. Strangely enough, Ayres has been the practice goalie for the team he would be facing, the Maple Leafs, and their top minor league affiliate for the past eight years. He had a kidney transplant 15 years ago and his future as a player in the sport was in doubt.

He was working as a Zamboni driver for the Leafs’ minor league team, the Toronto Marlies. For those who may not be aware, a Zamboni is the machine that cleans the ice between periods of a hockey game. It takes a driver to do the job. As a maintenance man at the Marlies’ arena, that was one of his jobs. Until last Saturday.

In his dream stint as an NHL goaltender, David Ayres allowed two goals on the first two shots fired at him. But he shut the door the rest of the way, making eight saves, preserving the Hurricanes 6-3 victory. He became the oldest goaltender in history to win his NHL regular-season debut.

David Ayres makes a save

He was mobbed by his teammates when he returned to the dressing room. Following the game, the Hurricanes announced they would be selling t-shirts with Ayres’ name and jersey number 90, with royalties going to their hero, and a portion of the proceeds being donated to a kidney foundation of Ayres’ choice.

Ayres mobbed by his teammates after the win

This is really a once-in-a-lifetime story.

Here’s a man in his 40’s, who had a dream that apparently wasn’t going to materialize. Circumstances was making it virtually impossible for it to happen. But ultimately it did happen. For one segment of time in one game.

For David Ayres, he finally played in an NHL contest. And skated off the ice as the winning goaltender.

And his moment occurred on the 40th anniversary of the Miracle on Ice. The improbable USA triumph over the Soviet Union in the 1980 Olympics.

If you ask David Ayres if he believes in miracles?

He would quickly say yes.

Walter Mitty lives.

David Ayres

____________________________________________________________________________

Visit and “Like” our Facebook page “Stockton Communications” and follow us on Twitter @DickStockton_1

Book Dick Stockton as a speaker for your next event or meeting!

Dick is a distinguished and honored sports commentator who brings more than five decades of award-winning, sports broadcasting experience to your audience.

Visit https://dstockton.com/meeting-planner-info/